Please note: due to changes in regulations and constant design developments, we sometimes need to change details such as binding and inlay materials.

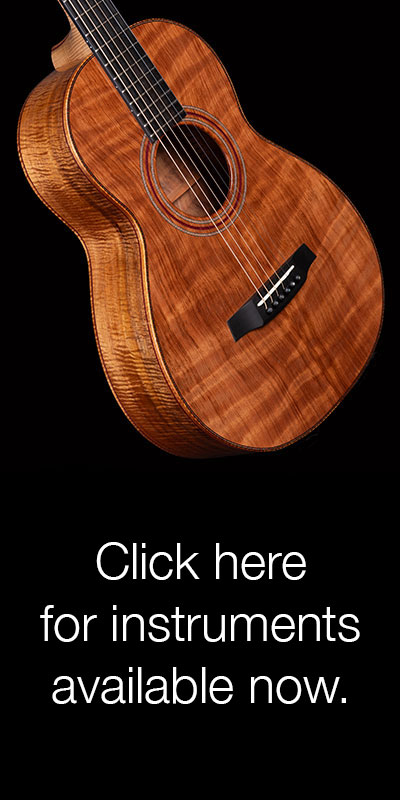

- Custom Guitars

Gallery 1: Falstaff & Others

Gallery 2: Falstaff & Others

Gallery 3: Alexander & Others

Gallery 4: Alexander & Others

Gallery 5: Ariel & Others

Gallery 6: Ariel & Others

Gallery 7: Mandolins & Others

Gallery 8: Mandolins & Others

Gallery 9: Unique Instruments

Gallery 10: Unique Instruments

- Personal Selection

Gallery 11: Personal Selection

Gallery 12: Personal Selection

- PLAYERS

Players

Bands

Players Gallery

Player's Comments

Guitar as Art

The Art of the Guitar

- ARTISTS VIDEOS

The Fylde YouTube Channel

- The Workshop Videos

The workshop Videos

- STRINGS THAT NIMBLE LEAP

Strings That Nimble Leap - VIDEOS - FYLDESTOCK

Videos of the acoustic gig to beat all acoustic gigs (perhaps). - FYLDE AT FIFTY :

The Video

- Roger Bucknall

History

Profile

Philosophy

- Roger Bucknall ... a guitar maker's philosophy

Built by hand

Design

Materials

Manufacture

Skills and experience

End Grafts and Details

Finish

Final Assembly

- Roger Bucknall's notes from a workshop.

Guitar Maker or Luthier

Tuning

Zero frets and intonation

Bracing and voicing

Neck joint

Fingerboard bindings

Neck straightness & Eulers columns

Necks, heels and bodies

- The Workshop

The workshop in pictures